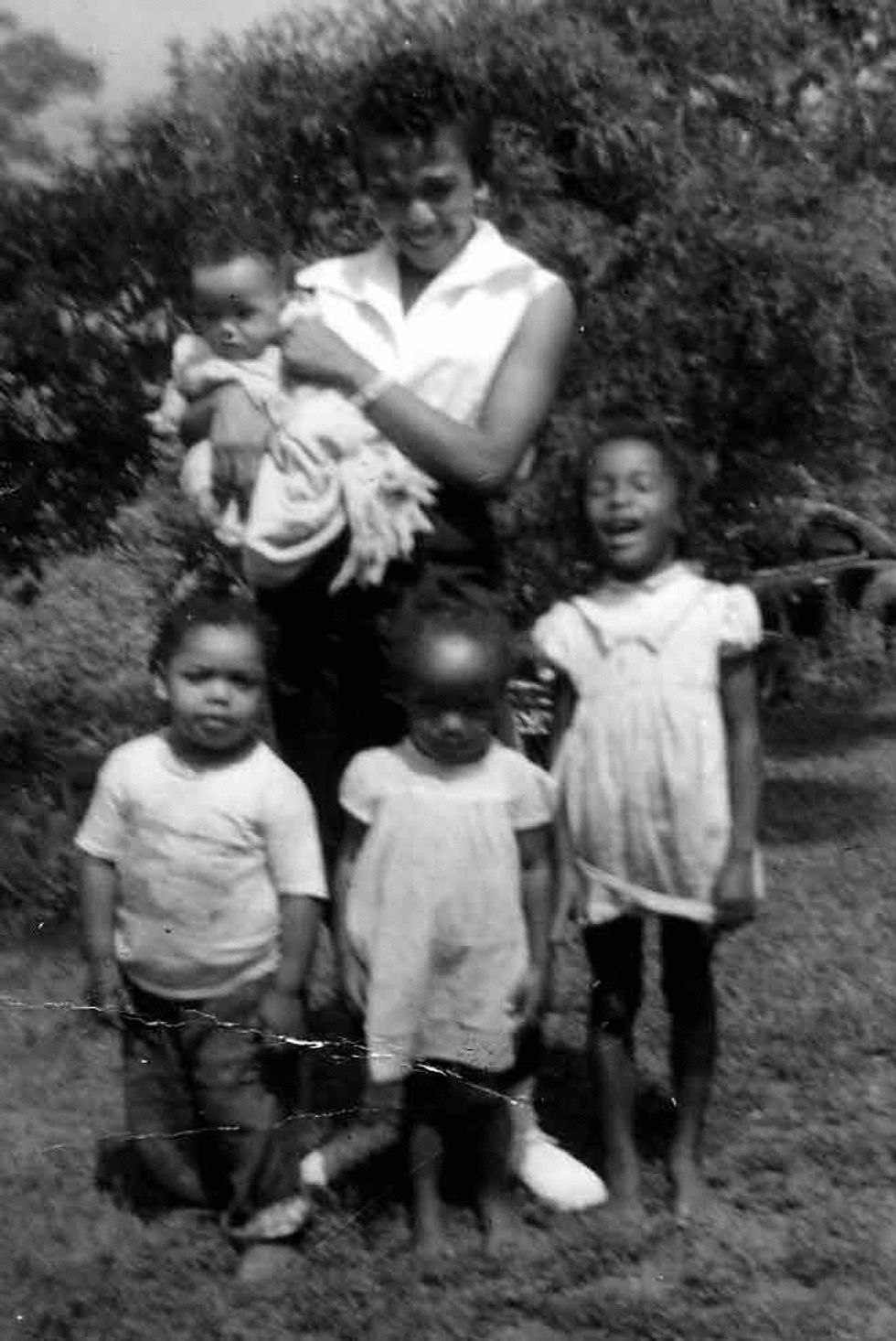

Courtesy of Carol Swain

Despite the chaos, a former professor-turned-politician finds hope in youth: "I get energy from young folks."

Yeah, well, you know, that's just, like, your opinion, man. —"The Dude"

The college students snap their fingers in unison. One of them yells at guest speaker Carol Swain and demands she wait until they finish! For months, the students have done everything in their power to get her disinvited from speaking here at Emmanuel College, a small Catholic university in Boston, down the street from Fenway Park. A palpable hostility radiates the air — or, rather, two hostilities: One from the students, and one from Swain, who seems to have enacted the Saul Alinsky principle of ridicule to infuriate her opponents — "opponents" is her word.

The students snap for a solid 20 seconds, with a Che Guevara scowl. It's clear that they see their snapping as warfare, but Swain just laughs, a grunting laugh that invokes her esophagus, as if she wants them to pick up on her nonchalance, her unflappability. The way she sees it, she can mock them and they can mock themselves but she cannot be mocked, and she will not be beaten.

Fox News hero and Prager U mainstay — heralded by the right as a black conservative who braved academia, whose life has been a series of miracles and disasters, who tried to kill herself several times when she was younger but now believes in God and plans to be the next mayor of Nashville, Tennessee. (She'd be the first black woman to do so.)

Her story, how she rose from the hellish lows of poverty to become an Ivy League professor and author and talk show host and political pundit, is about as American as Route 66 diners. Her resume is longer than this profile. Awards, grants, fellowships, honors, many of which include words like "lifelong" and "permanent." Yale. Duke. Princeton. Virginia Tech. North Carolina. Vanderbilt. Documentaries, keynote speakerships, panels, books, articles, appearances on CNN, Fox News, C-Span. She was name-dropped by the Supreme Court — twice. Her book, "The New White Nationalism: Its Challenge to Integration," which eerily predicted the rise of the alt-right and its pseudo-intellectual racism and sneering identity politics, was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize.

What percentage of controversy does someone need in order to be famous? It's not zero, and, with the exception of Donald Trump and Kanye West, no one can survive 100. Swain comes in at about 50 percent, just as famous as she is infamous. The Southern Poverty Law Center has repeatedly featured her on its "Hatewatch," labeling her an enemy of the LGBT community and an apologist for white nationalism (she wrote about it in an op-ed for the Wall Street Journal). Swain has a 4/5 rating on RateMyRacistProfessor.com, which is an actual website.

More than once during her academic career, students demanded she be fired. Petitions. Op-eds. Satirical cartoons. In 2015, while she was a professor at Vanderbilt, her article about Islam provoked campuswide protests, which the university meekly supported, denouncing Swain in the process despite her having tenure. She was flooded with hate mail, some of which contained death and rape threats, including a box labeled "Fondle with care." Inside, a phallic-shaped cutout with the words, "You need to loosen up."

So today's angry college students are nothing new for Swain.

A few weeks ago, she told you in an email that she'd reduced her rate to a fraction of what she normally charges "because of one determined student who wouldn't give up," then she quoted Isaiah 40:31: "But they that wait upon the Lord … shall mount up with wings as eagles; they shall run, and not be weary; and they shall walk, and not faint."

Every time another protester asks a question, some weird surge of adrenaline rushes through the other students. They groan, they cross their arms as they roll their eyes, they laugh in sarcastic disbelief, they ask unanswerable questions then get pissed when Swain doesn't answer right away.

"I've always been ahead of my time," Swain told you earlier, with an elusive smile. "I always had a feeling that there was something I had to do. I always had a sense of urgency and I was always serious."

She often talks about how she was predestined to be famous — not just by merit, but as an act of God, as a lottery-like selection from above. This strikes you as a crafty approach. A God-destined path defies any sort of dissent. If God himself has paved the way, you're just following orders.

She shuffles in her waxy-yellow high heels, sneaking glances at a legal pad, in the same pastel-yellow blazer and yellow zebra-print blouse she had on earlier, as she repeats the speech she gave you five hours ago at the restaurant.

"College is no longer about education," she says. "It's about teaching people what to think and just have them regurgitate that back. It's really a misuse of money. And there are so many fields that people can major in and those fields are totally useless. Gender studies, women's studies, ethnic studies, all those things are egregious."

She laughs. Nobody else laughs. "Might as well call them the Egregious Studies Department."

She laughs some more. "And then people wonder why with a bachelor's degree they can't get a good job: Because they're not trained to do anything but protest."

Her voice undulates with a Virginia accent. She talks slow, in a charming, half-refined way. The vowels blend together, combed through by sighs that fade into nothing. Occasionally, she snorts after finishing a sentence. And, anytime she sits down, she rubs her knees in what at first seems like a nervous or compulsive motion, but turns out to be something she just does.

You had expected an auditorium but this is just a normal room, with a lectern facing rows of chairs packed with students. A hundred or so, and another 80 standing. There are two distinct groups of students. The students in the front rows are clearly pro-Swain: well-dressed, attentive, mostly girls, with three boys in suit-and-tie. The rest of the students (the majority) scowl, with a variety of neck tattoos or half-shaven heads or horseshoe nose rings, and a few of the boys wear pink or yellow lipstick and layers of rouge on their cheeks. You chat with people from both groups, and every one of them is genuinely kind.

*

Five hours earlier. You and Swain wedge into a booth at Longwood Bar & Grille, the fancified second-floor restaurant of the Inn at Longwood at the Medical Center. Drab piano music putters along, just barely louder than the clank of whiskey glasses and the hum of different NFL games. Designed to look like a pub. Battered red carpet. This place smells awful; rank and bare and ugly like a small-town casino.

"They got me the cheapest place they could find," she says, then laughs, softly. "You can tell they didn't want me to come, can't you?" She tilts her head, "It's all good, though. I'm just glad I got here."

Then she tells you that she's running for mayor of Nashville. She says it like you didn't already know, but both of you know that you already knew.

"I never ever in my wildest dreams thought I'd be running for a political office," she says, and you're not sure you believe her.

She adds that the Nashville election is irregular because the last mayor, Megan Barry, the city's first woman mayor, resigned in disgrace. Embezzlement, felony theft, adultery. She'd been having an affair with her bodyguard, who she kept on salary at about $100,000. They took trips together. Places far from Nashville, like San Francisco and Athens, Greece.

Over Swain's right shoulder, a garage-park food court thrives, full of off-brand restaurants. Clearly, there's a hospital nearby, because a good two-thirds of the people wear scrubs and look exhausted and Carol Swain is running for mayor of Nashville, a fact that she'll repeat at least two dozen times by the end of the night.

*

"Spiritually, even growing up, I never felt that I fit in," she says. "I had a crippling form of shyness that would affect me for the rest of my life. And so part of my story is a struggle for a voice."

Behind her, 1980s-arcade-game graphics plaster the booth's high walls, gaudy neon that gobs across drab vinyl.

"Since [the students] didn't want me to come, since they're liberal, I thought I would make them endure the story of my life," she told you.

Swain began at the bottom of things in the abject poverty of rural Virginia, the second of 12 children, all crowded into a shack without running water. Her mother refused to accept welfare of any kind, including school-provided lunches. Swain was a high school dropout, married in her late teens to "an older neighbor," then a mother of three, two boys and a girl who died of sudden infant death syndrome.

After a few dark years, she went to community college, then earned an undergraduate degree, then a graduate degree, then a doctoral degree. She landed a series of professor jobs at elite universities. Suddenly, at a young age, she was a hot shot.

"I knew it, too," she tells you, "I knew how I looked."

Her makeup is smooth and fluid, and the only visible wrinkles — her deepest — originate from smiling, tiny crescents at the drape of her eyes, evidence of a deep optimism.

"I've always done the opposite of what people say," Swain tells you. "I've always been different. I was born kinda different. But I was shy. Most of my life. Even when I was at Princeton."

She says that all of the other professors at Princeton spoke in long bursts that eventually led into sardonic put-downs. It annoyed and intimidated her. The longer she stayed, the more silenced she became. Then, she says, the other black professors turned on her.

"They didn't see me coming," she says. "All of a sudden there was this black professor at Princeton that they didn't know, that didn't go through their ranks."

They called her a sell-out. Told her that people hated her. Said the only reason she had made it this far was affirmative action. That got to her. "I would pull out my resumé and think, 'Well maybe I didn't do this stuff. Maybe they're right.'"

II.

You shuffle outside, immediately stung by the cold. The sun is out, but there's an ugly scatter behind it. Blue skies, with white clouds, curdling at the bottom, ready to spill down rain. In a matter of 30 minutes, a cold grey shrouds the city of Boston, and dark violet unpeels the sky, and after that the sun doesn't return for a week. It's mid-April, which is usually springtime in Boston. But this winter was by all accounts a brutal winter. Former first lady Barbara Bush died last night, and the Boston Celtics lead the Milwaukee Bucks 2-0 in the first round of the NBA Playoffs.

Emmanuel College is gated, fortified near the Charles River, and as soon as you see it you mumble the word "Expensive." Eventually you wander the Administration Building, into a hall overflowing with people as Swain is speaking.

"It just happened gradually, then it happened so fast," Swain says. "I've been a professor almost 30 years, and I saw the changes begin — soon as [Barack] Obama got elected, is when it really got on steroids, but I think the groundwork was laid before that."

At first, most people stay quiet. They listen. But they wiggle a little more with each minute. They're desperate to start the Q&A. Some of them clench notepads into balled-up fists and groan as they write down something Swain just said. An ambulance whistles past outside, sirens carried loudly through the room by a cold draft. After a moment, the room gets quiet again and Swain tries to ease the tension with a joke about how, if only she'd given a trigger warning she would have been welcomed by these snowflakes. The silence. All tension. The opposite of laughter. "Oof," you say to the woman beside you.

Then Swain says that she wants to tell her story. Then she tells her story. And it reminds her of J.D. Vance:

"The guy that wrote "Hillbilly Elegy," she says. "This white guy that went to Yale, that came from dire poverty in Kentucky. He went to graduate school and he was like a fish out of water. He was nothing but white trash, his family was nothing but hillbilly, but he talked about that honor code. He also talks about how poor whites are like inner-city blacks, that they have a code that they just don't wanna work," that sentence provoked literal gasps, "and there's an underclass, and he was able to escape all that, because his grandmother was really stern, but she was totally hillbilly. They were the kinda people that would pistol-whip somebody."

At the back of the room, a slant of professors in sweaters lean into a poker table covered with store-bought cookies, bottles of water, and an assortment of processed meats. The professors are trying with a gymnastic intensity to seem relaxed, arms crossed past the armpits. Then Swain brings her story into present day and says that she's running for mayor of Nashville and God himself ordained it.

*

"Spiritually," she says, "the person that pleaded with me on April 1st, Easter evening, had been trying to get me to run for mayor for a long time and I kept saying 'No no no'."

"Just pull the paperwork," he told her. "You don't have to turn it in.'"

That night, she prayed.

"The next morning I woke up with 12 issue positions that I thought were important for Nashville," she says. "Those are the positions on my website." She wrote them in a notebook where she also keeps her prayers.

Down the hall, people lean forward during evening Mass in the chapel between classrooms and offices. It arches up four stories, the innards of a basilica. More than a room, more like a Gothic cathedral. The air inside has a sacred intensity. Meanwhile, half-a-football-field down the hall, students doubt whether God exists at all.

*

By far, the most outwardly incensed student is the self-identified gender-nonbinary person in a Red Hawaiian shirt with a weed-leaf imprint. Crew cut gelled at the top, and floral tattoos, soft yet rocky, the length of their arms. Buddy Holly glasses and a snarl that contains both the bravado of young Elvis and the depravity of later Elvis. The person leans into the wall, occasionally scribbling into a reporter-style notepad and shouldering the concrete like it's a bad guy.

Swain fumbles her speech to an end, then starts the Q&A. A glow in her eyes: She is just as ready for blood as the protesters are. This feels like the main event, like the speech was just a formality.

Immediately, the gender nonbinary student says: "How can you defile welfare and at the same time belittle the culture of underprivileged peoples of color and disenfranchisement being murdered by oppressive institutions that — ?"

Swain cuts off the protester, talks over them, raising her hand in the "Shut up" motion, then fires back with the story about her mother refusing welfare, mentions the deleterious effect that government assistance has had on her siblings. And when the student tries to respond, Swain slaps the air and says, "You have probably never been told this but I've heard enough from you and it's time for you to be quiet. Next question."

The student clenches fists and groans and tries to interrupt again. But Swain has moved on, so the protester stomps out of the room, mumbling to each person they pass and gripping their belt loop and suspenders.

*

"How can you call yourself a Christian and not like Marxist doctrine?" a student asks Swain.

"I don't understand the question."

"You mentioned that you worship power — ."

"I said I studied power," Swain replies, lifting her hand to stop the girl from interrupting. "Because it's important to study the ideas of the world."

"Whatever," the girl says, with an eye roll. "So basically you hate Marxism but, like, love power. But power is power."

She gawks around at her peers, as if devastated that they haven't praised her. She repeats herself, louder and more exasperated: "Power is power, okay? Power is power!"

In unison, the students begin snapping, in unison and protest, then the questions resume. Swain derides each fallacy, and enjoys it, though, to be fair, not without committing a few of her own. She does it — all of it — combatively, with confrontation in mind. Fight them with their own dirty moves: Everything is relative and feelings are facts and disagreement is an act of violence. She has perfected the art of identity politics and microaggressions and has weaponized both for provocation.

When one of the white students, a man, starts telling her that she is delusional for believing in capitalism and "other systems of hegemonic subjugation and oppression...."

"Are you really verbally assaulting a woman?" Swain asks, with a scowl. "A woman who could be your grandma? What gives you the right to verbally assault a black woman? Do you have a problem with black women in a position of power? Or is it just black people in general you dislike? And with my life. Living in poverty, no running water. Hah! Oppression!" She grunts.

"Oppression is being so poor and hopeless that you can't make it through high school. If anyone in here can talk about oppression, it's me, and I'm proof that the 'system' you have in mind will only keep you on welfare and spending money on who knows — if you're lucky." She points to herself. "I am all the proof you need."

The student's eyes bulge in terror as he collapses into his seat. It's no coincidence that the only people who get truly confrontational with Swain are young black women, all convened in a line, shoulder-to-shoulder down the row. At the perfect moment, they stand up in unison. Several of them had asked questions earlier, each time with the quivering voice of an angry, over-prepared 19-year-old, but now they would stand together.

Swain answers the first question, something about her stance on incarceration. "I believe that whites and blacks have far more in common than most people believe and —"

But the women interrupt her and shout their questions one at a time, and when Swain tries to answer, they shout back that, "No, no, you need to listen."

The rest of the student protesters cheer as the young black women insult the black woman in ways that remain off-limits for all others, a troubling dynamic not unlike the battle royal in "Invisible Man." By now, most of the room is standing. When one of the women shouts "Black Lives Matter," the room erupts in chants. But all the slogans are different. Without any organization, there's no overall message, just chaos and noise.

One of the suit-and-tie front-row guys leaps up, says, "Dr. Swain only has time for one more question."

This infuriates the protesters, who continue to shout all at once. Then they really lose it when Swain, for her last question, points to one of the neatly dressed women in the front row, who asks Swain a total softball question. Then the nicely dressed guy says, "All right, that was the last one."

The protesting students disagree. They want Swain to know that they will ask as many questions as they like, for as long as they please, and what right does she have to ignore them when they have plenty more to say?

III.

After teaching at Princeton, following a baptism and a shift in politics, Swain was hired at Vanderbilt, where she would take her fight against academia to the breaking point.

"I like to say they hired one person and another person showed up for the job," she told you.

Once there, she took any sign of hostility as a challenge — her rebellious spirit at work. In tense situations, when many academics might have quietly receded into the bushes, Swain goaded, poked, antagonized; all part of her strategy to become the conservative Saul Alinsky, whose "Rules for Radicals" has served as an instruction manual for the politically rambunctious.

"My favorite rule is 'Make your enemy live up to his rule book,' and 'Use ridicule,'" she said. "There is a place for the person that's gonna use ridicule and challenge the administrations of colleges to make them live up to their rule book. And that rule book is the college handbook, and the mission statements, and all those lofty things they claim they stand for."

In response to the Charlie Hebdo attacks in January 2015, Swain penned an article for The Tennessean titled, "Charlie Hebdo attacks prove critics were right about Islam." (It reveals a lot about Swain that, in response to the horrific attacks, she didn't write about free speech or terrorism or even Western values.) The article is short, barely more than 500 words, but, for the Vanderbilt community, the message was strong enough to cause an uproar.

The campus erupted in protests, which is itself an interesting reaction given the overall context: Charlie Hebdo, a satirical magazine known for flamboyantly using free speech to deride every doctrine, orthodoxy, government, and religion, was attacked by Islamic State-affiliated extremists who were so enraged by the magazine's satirical artwork that they murdered 12 Charlie Hebdo staff members.

A week later, in a show of free speech, Swain criticized Islam in an op-ed, which disproportionately enraged Vanderbilt students, leading to above-mentioned death- and rape-threats. In other words, the students' outrage can be syllogistically linked to an anti-free-speech stance that lands them on the side of homicidal terrorists. Obviously, their reaction pales in comparison (by far!), but there is something unsettling about how the students were more outraged by Swain's ideologically-guided words than by the terrorists' ideologically-guided murder spree.

"Then the LGBT people decided that I was a threat to Muslims and LGBT people," Swain said. "They invented that."

A few months later, she criticized Black Lives Matter during a debate on CNN. "I said, one of the reasons young black men get killed is they resist arrest. Then the black people on campus got mad."

A friend contacted her, "Congratulations, you've united the campus."

After Swain authored a series of mocking and intentionally offensive posts on Facebook, Vanderbilt students took to change.org and demanded Swain be fired. Not to be outdone, Swain responded in an interview with a local ABC station, describing the students as "sad and pathetic, in the sense that they're college students and they should be open to hearing more than one viewpoint."

The students then demanded that "Vanderbilt administrators confer with the American Civil Liberties Union to create and mandate a diversity training program for all Vanderbilt faculty – including Professor Carol Swain."

Swain responded on Facebook: "Only an idiot would think a 61-year-old black woman who has spent much of her life in academia would benefit from sensitivity training."

IV.

About 9:30 p.m., Swain and the neatly dressed students from the front two rows all shuttle to a dimly-lit sports bar nearby. You walk, alone. Each draft has an ice-whip of Atlantic Ocean. Your teeth chatter and your bones grow wooden. You duck into Sal's Pizza. A high school team is playing at Fenway tonight. It's 1-1 in the 6th inning. The grounds crew, in matching red jackets and Red Sox beanies, have snuck out to get a pizza slice. They groan and say the game is so boring. "He just slid into second, did you see that, he didn't even need to, he was just as bored as everyone else!"

You ask if it's normal for a high school team to be playing at Fenway Park on a Wednesday so soon after the start of the MLB season. "Let's just say it is if your daddy is a certain someone, with a certain sized wallet and a certain influence on town, feel me?"

The Mafioso vagueness has you nodding in awkward confusion. "Yeah, power is power," you say, then cringe. Then you trek back outside then move along. Maybe it's because, on Monday, an American won the Boston Marathon for the first time in decades, or maybe it's always like this, but everywhere you look, people are jogging. Always. At all times. In all places. Even when you round the corner into the restaurant, you have to dance through two joggers lit up in their spacesuits.The place is crowded. It takes you a moment to find Swain, but then you see her waving in her bright yellow blazer. The music is so loud that the bar's tinted glass wobbles decoratively. The students have filed in around Swain, around the oblong table, with Swain prim at the middle, like a Facebook rendition of "The Last Supper."

*

The students lean toward Swain, barely able to hear anything over the Taylor Swift track — which seems to jut from everywhere, a cavalcade of sound. Look, look what you made me do. Nothing in the place has as much authority as the music. Even the waitstaff lean in when they're talking, even they haven't gotten used to the volume. Platters rush through the air, saddled onto shoulders. The waiters are dressed all-black, so it's like the trays are floating, and the steam and the delightful stink of bleu cheese hover past like kites with free will. Blame it on the loud music, but Swain is only able to talk about the Nashville campaign. Does it always cul-de-sac back to her and her poll numbers? So you talk with the two young men and the one young woman near you.

"I am about to go to med school. I wrote a model detailing the accumulation of plaque in the brain resulting in dementia!"

"I am from Maine, a town with a population of 350 citizens, and Boston is exciting and I have worked hard to find the good in things, and there it was all along: Here in Boston!"

Each of them weaves through the concepts and theories and universe-brightening ideas that illuminate a college student. The two young men rejoice that restaurants in Boston stay open past 6:30 p.m. and show you their pocket knives. All of the students have an air of unhatched success. You shirk back, with a glimpse of how the world has changed. Growing up, politics were a flighty, off-hand thing. They weren't the premise of each conversation like they seem to be lately. And you could get along with someone who held differing opinions without the slightest concern — you might know a person for years before politics ever even came up.

*

A Bruce Springsteen song fades out, and it's quiet long enough for you to hear Swain's grandiloquent twang. She recites. She talks about certain things. While conversations around her change, she returns to herself and what her life means, in the grand scheme of thing. Of course, that's why she's here in Boston to begin with. But also maybe she's a closed circuit. Conversations always returns to her accomplishments (there are tons), to her life (it should be a Hallmark movie), and to her genius in attacking the very system (academia) that made her an authority on disdainful systems like academia.

The music is deafening. You nod at the waiter, "Just bring me a big beer!"

"A big one?"

"Big beer," you holler. "Real big! Very thirsty!"

You look at Swain, who despite the occasional bout of arrogance or venom is most of all charming and sweet. Maybe that's just who she is: A motherly type, with an unwell mother, and here she is with these sweet, attentive young folks — who themselves feel alienated, lost in a world of social upheaval. Each of them says it, in many ways: As right-leaning college students, they often feel voiceless and outnumbered, the target of intimidation, sometimes even by their professors. Each of them, in one way or another, details a history of responsibility, of hard work and conviction. Most people their age, in their situation, college-age in Boston, would use a Wednesday night mid-semester to plow through some watery beer or weave along backroads in a friend's red Miata with a joint.

But no. The group of cheery, polite, good-postured college students have the style and attitude of a Tuesday work meeting, as if they were born this way — so sturdy and austere — as if they skipped ahead to adulthood by choice and never thought about it again, all of which creeps you out a little: you feel the urge to take them to get tattoos or drink wine and eat mushrooms. They've got money and success in their postures, waiting. They are all so grown up. No doubt, they'll run companies and win awards and become surgeons and lawyers and maybe earn a seat in Congress — perhaps more. They are responsible, they are engaging, they are kind.

Hopefully, they can get away with it, can jet past the developmental weirdness of their 20s and tackle careers and achieve success without a wince of regret. Hopefully, they don't reach their 50s and succumb to a gurgling resentment of having never been wild. Or maybe it's you who are the problem.

Before you can parse the thought further, the waiter arrives with your beer. The students immediately giggle as the waiter lowers it, gripped with both hands: An outlandish, Dr. Seuss configuration of glass, a statuesque arrangement taller than the table.

After a series of What did you say's and Huh's, you learn that you inadvertently ordered the signature drink: A yard of beer. You look at the table and realize everybody else ordered water. Only a few of them are even 21. It's impossible to drink beer from a massive funnel cake of glass without feeling ridiculous.

One by one, the dishes arrive. Swain and the students sit politely, waiting for something.

One of the phrases Swain repeats, "I get energy from young folks." These young folks no doubt have an energy. A presence much different than that of the students from earlier with their Snapchat scowl and their weeknight parties — although, the protest crowd is not without its own charm, a charm, admittedly, more age-appropriate, uninterested in suits and formal dresses.

All at once, you feel the glow of attention and it takes a moment for you to realize that everyone else has clasped hands. The relief you feel, the calibrated warmth — that's their energy. It is definite and seemly. At a bar, near a college, next to Fenway Park, amid the chaos and the shouts of people gulping Jager shots, with the air-conditioned scent of chargrilled burgers, in a dark room, under a tide of music, as the rest of the place paces drunkenly, each of you leans forward into prayer.

As you grasp hands and pray with the group, Depeche Mode's "Personal Jesus" blasts loudly. Somehow, it's more sacred than it is ironic and hilarious. Although, it is incredibly ironic and hilarious. "Personal Jesus," which lyricist Martin Gore described as "a song about being a Jesus for somebody else, someone to give you hope and care," is a perfect image of the situation, with these young folks, who feel silenced and adrift, clasping at one another's hands so defiantly, so unafraid of mockery — in the presence of a woman they've admired, a woman who has helped them feel less alone.

The young person who'd been praying says, "Amen," and everyone unclasps hands then begins unfurling silverware. A month from now, Swain will lose her bid for mayor of Nashville. Second place. With 23 percent of the vote. Abruptly jobless, she'll take her mother to church every Sunday like she always has. You'll keep in touch with her. She'll even visit Dallas and appear on Glenn Beck's podcast. Occasionally, she'll ask about this profile, curious if it's ready. But for now, she's still electric with hope.

"Wait, wait," Swain says, still holding hands with the girls at each side, "I'd also like to say grace."

You look at Swain, her lambent smile and tranquil brown eyes and a soft light behind her, then turn to the young folks beside you, their hands open, hanging in the air. Nod. Smile. Bow your head. Close your eyes — reach out and touch faith.