Photo by Sean Ryan

Up close with the Castro campaign

El Malecón Events Center and After Hours Club sits slumped behind a dumpy Git-N-Go, around the corner from Val Vista Trailer Park and New Hope Open Bible Church and Romantix, which was once voted Des Moines' "Sexiest Adult Boutique." In Spanish, "malecón" means "a stone-built embankment or esplanade along a waterfront." No obvious connection existed between El Malecón, the building, and malecón, the word.

Not a single stone in El Malecón, mostly drywall and plywood. The nearest body of water was a man-made lake frequented by pontooners. El Malecón was 800 miles from an ocean. But as evening shuttled darkly over the building's sagging roof and blacked-out windows, semantics didn't matter.

If you listen to "Seabird" by the Alessi Brothers outside El Malecón, on an August noon, you can catch the point in the sky when day tips into afternoon.

Inside, it was all drenching shade. For some reason, there was a bouncy castle at the back of the room. Children screamed over the generator and the rush of air and inflation. The balloon colors brightened a rig of Corona signs and tired bartenders, who glanced periodically at Julián Castro holding court beneath a disco ball.

Castro strained to focus as Kenny Loggins' "Danger Zone" boomed from mounted speakers. Surrounded by banners for his 2020 presidential bid, he barely moved as everyone else nodded to the words:

Out along the edge,

Is always where I burn to be.

The further on the edge,

The hotter the intensity.

All you could hear were music, kids' yelps, and the occasional fumbled beer glass.

The meet-and-greet had started four hours ago. Now, it was 9:00 p.m., the second Thursday in August, opening day of the Iowa State Fair, where Castro would be speaking the next morning.

He may have looked tired, but he also looked sharp with his white button-up with the sleeves rolled and his strong handshake, his hair flawlessly pomaded.

Twenty-somethings in blue "Castro" T-shirts folded chairs and untied banners. Most people had left, all but a dozen or so, clumped into a line. Castro spoke to each person, all Hispanic, mostly men.

In that half-light, Castro looked like he had sped through life without adventure. This was probably not the case. And for a guy who conservatives often consider hateful or combative, he was friendly, if a bit reserved.

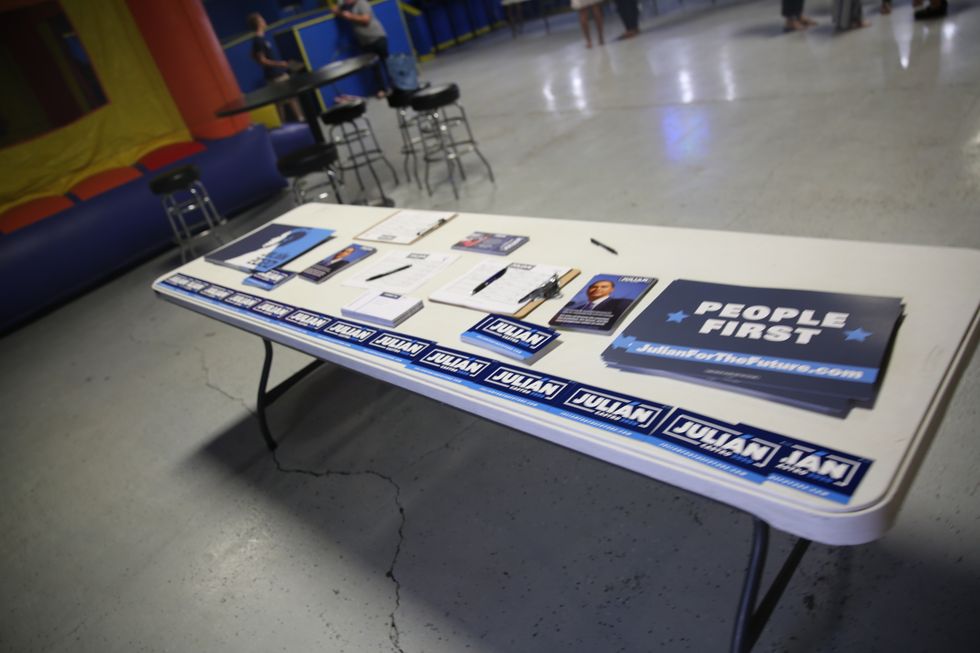

Castro's campaign slogan adorned the walls: "One nation. One destiny." Various Castro stickers, signs, and momentos covered a poker table by the entrance.

The night before, Castro was all over CNN. His campaign had tweeted a picture with the names and occupations of 44 San Antonio residents who'd donated to President Trump's 2020 campaign, adding that the people's "contributions are fueling a campaign of hate that labels Hispanic immigrants as 'invaders'." Conservatives decried it as doxxing and warned that posting Trump supporters' personal information would put them in danger. Dirty gaming, on Twitter no less. Liberals, surprisingly, pivoted into a conservative stance by calling the tweets free speech. The information was freely available, after all.

As the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development, Castro was the youngest member of former President Barack Obama's Cabinet. Before that, he was the mayor of San Antonio; before that, a member of the city council. Meaning, in 13 years, he expanded his power from the county level to the federal level, earning a seat near the most powerful man in the world, and now he was vying for his shot to earn that spot himself.

His twin brother, Joaquin Castro, also a Democrat, serves in the House of Representatives for Texas 20th Congressional District. Like many twins, the brothers look and act enough alike to make you squint, and different enough to make a career doing the same thing.

His mother is controversial civil rights activist "Rosie" Castro, who had joined La Raza Unida, a political party that sought to elect more Hispanic people. Castro's brother and mother introduced him at the San Antonio rally where he announced his bid for the presidency. In doing so, he'd signed up for a gold rush. 2019 had barely started and here was another Democratic candidate vying for the 2020 White House.

If Castro were elected President, he'd be the first Hispanic to get the job. And young, 44. Sharp. But everybody was saying that Castro didn't stand a chance, stuck at 1 percent in the most recent polls.

I had trekked 800 miles to follow the Democratic candidates around Iowa. My dad came along. The man had never held a proper camera before but would he be my photographer? Earlier, at the Joe Biden event, he proved adept at photography. A maniac for the perfect image!

Eventually, he wandered up to Castro, whose campaign manager smiled and asked if we wanted a picture with "Julián." Without answering, my dad extended his hand toward Castro. "I'm from Ireland," he said. "And I want you to know that my heart aches for El Paso, for what happened in El Paso."

Four days earlier, a psychopath killed 22 people at a Walmart in El Paso. He'd posted a manifesto full of bizarre and contradictory political ideas.

A mere 13 hours later, another psychopath killed 10 people, including his own sister, in Ohio. It was the kind of terrible that filled your gut with darkness and made you wonder why, why, why. The shooters had designed their attacks to be explosively political. Everybody was nervous. Everybody kept wondering, "Who the hell would do something so heinous?" Politicians took it upon themselves to answer this question. They had to. Beto O'Rourke even canceled his Iowa appearances and stayed in his hometown El Paso, although many people had begun to speculate that O'Rourke's campaign was collapsing.

When my dad said "El Paso," Castro had a graceful down tilt to his face and an immediate crestfallen slump in his eyes. It was the perfect display of empathy and sadness, with a dash of hope in there, because nuance is presidential. Then he said, "That's why I will make an excellent president."

Outside, my dad smiled. "I didn't want to tell him that I can't vote," he said. He is not an American citizen, but Irish. "I just wanted him to know that he wasn't alone. That El Paso is weighing on all of us."

A food truck puttered in the parking lot, and the sun declined into an ocean of violent red. We were not far from the birthplace of John Wayne, 30 miles. Out where the world gets so quiet all you hear is birds and shush and the occasional green tractor ribboned with corn husk. Iowa retains an enduring, motherly spirit, like those birds that can fly for a year without landing, their saffron beak slicing the clouds.

Alessi Brothers - Seabirdwww.youtube.com

New installments to this series will come out every Monday and Thursday morning. For live updates, check out my Twitter or email me at kryan@mercurystudios.com